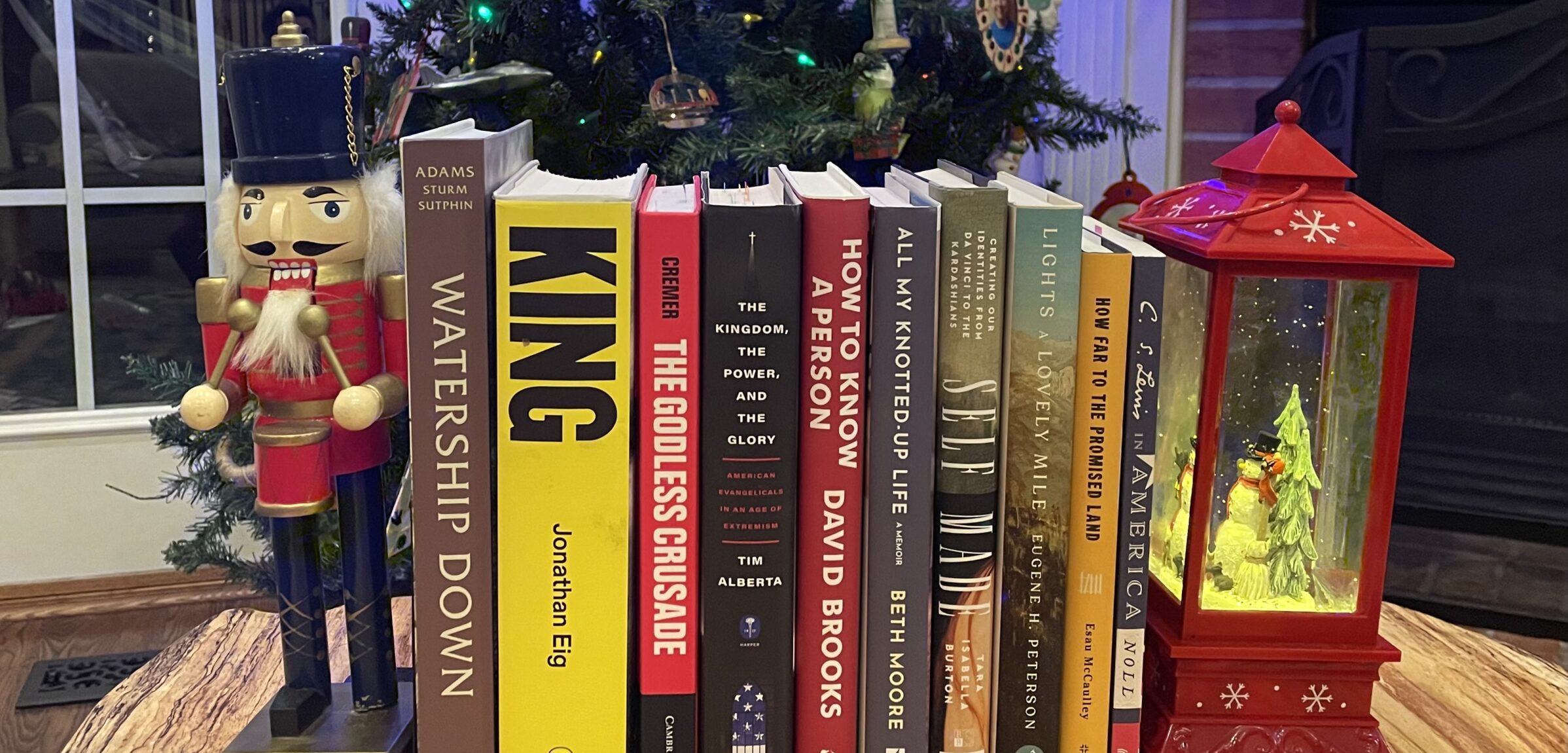

Every year I cobble together a list of my favorite books of the year. For many years, I had a rule that I would never include books written by friends. As you can see, I’ve tossed that rule aside—largely because I kept breaking it. The list usually skews more to the non-fiction side, even though at least half my reading is probably fiction and poetry. That’s because I limit the scope to those books published in the last calendar year, and I usually find that the fiction or poetry I like has been published before that.

The list is in alphabetical order by author’s last name—not a ranking of first to tenth. I tell you why I like the book and then give you a quote from it to give you a sense of the vibe.

1. Richard Adams, adapted and illustrated by James Sturm and Joe Sutphin, Watership Down: The Graphic Novel (Ten Speed Graphic)

Once, I mentioned the novel Watership Down and a young man said, “Yeah, I read that when I was a kid. It was really sweet.” After a couple of minutes of confusion, we realized he was thinking of The Velveteen Rabbit. The rabbits in Watership Down are anything but velveteen. The book deals with the darkest aspects of human existence projected onto the lives of warrens of rabbits—murder, envy, rivalry, exile, scapegoating.

That’s why I loved this graphic novel. The artwork captures what the book is attempting: to give the reader the vertigo of seeing animals we are acculturated to view as harmless while at the same time seeing the tension, peril, and depravity that we pretend we don’t see in ourselves. The last page, particularly, is astoundingly beautiful.

“All the world will be your enemy, Prince with a Thousand Enemies, and whenever they catch you, they will kill you. But first they must catch you—digger, listener, runner, Prince with the Swift Warning. Be cunning and full of tricks, and your people shall never be destroyed.”

2. Tim Alberta, The Kingdom, the Power, and the Glory: American Evangelicals in an Age of Extremism (Harper)

This one was hard to read because I am a “character” in a lot of the story. And in this story, American evangelicals make the Watership Down rabbits look like the Easter Bunny. Alberta examines what happened to American evangelicalism in the Trump era, in venues ranging from Liberty University to the Southern Baptist Convention to a prosperity gospel preacher’s revival tent.

Meticulous in research and gripping in storytelling, the most powerful aspects of this book are rooted in the personal backdrop. At the start of the book, Alberta—a pastor’s son—recounts being handed a note at his father’s funeral from one of his father’s congregants, rebuking him for reporting critically of Donald Trump. When he showed it to his wife, she “flung the piece of paper into the air and with a shriek that made the church ladies jump out of their cardigans, cried out: ‘What the hell is wrong with these people?’”

This book asks and answers that question.

“Instead of testifying confidently to the presence of a supreme and sovereign God—a celestial chess master rolling his eyes at our earthly checkerboard—Christian conservatives have acted like toddlers lost at the shopping mall, panicked and petrified, shouting the name of their father with such hysteria that his reputation is diminished in the eyes of every onlooker.”

3. David Brooks, How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen (Random House)

The day that former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger died, someone posted a piece from The Weekly Standard that David Brooks wrote well over 20 years ago—a satirical piece on how to become the next Henry Kissinger. The piece was funny and insightful and skewered a certain kind of Washington pretension. The piece said to the real and would-be Kissinger-types: I see you. I know what you’re doing, and it’s ridiculous.

I cannot imagine David Brooks writing that article today. That’s not because he is any less provocative or alert to hypocrisies and foibles. His writing has changed, it seems, because his definition of the sentence I see you has deepened and widened. He is—like one of his most-quoted public intellectuals, Reinhold Niebuhr—a “tamed cynic.” This book is about not just taming but transforming.

The book, in typical Brooks fashion, examines the issues from a wide range of vantage points: brain science, psychology, ancient philosophy, world history, popular culture. In addressing the question of empathy, Brooks deals with practical wisdom as well as theoretical insight: how to have a conversation, how to ask questions, how to wrangle one’s personality in ways that expand rather than diminish others. “Empathy” in this book is not a vague emotional setting or a polite set of social skills but a way of moving through a broken world with one’s soul intact. This book changed the way I see “seeing.”

“Paradigmatic thinking is great for understanding data, making the case for a proposition, and analyzing trends across populations. It is not great for seeing an individual person.

“Narrative thinking, on the other hand, is necessary for understanding the unique individual in front of you. Stories capture the unique presence of a person’s character and how he or she changes over time. Stories capture how a thousand little influences come together to shape a life, how people struggle and strive, how their lives are knocked about by lucky and unlucky breaks. When someone is telling you their story, you get a much more personal, complicated, and attractive image of the person. You get to experience their experience.”

4. Tara Isabella Burton, Self-Made: Creating Our Identities from Da Vinci to the Kardashians (PublicAffairs)

Sometime in mid-2016, I heard myself say with sarcasm to a friend, “I, for one, welcome our new Kardashian overlords.” What I was lampooning was a world in which really serious areas of responsibility—from leading a congregation to holding the nuclear codes—seemed trivialized to the point of a badly scripted reality television series. Bless my heart: I thought it was temporary.

Tara Isabella Burton wrote Strange Rites, what I believe to be the best work of our time on emerging spiritualities. In this new book, she interacts with Charles Taylor’s claim that the secular age is one of “expressive individualism.” Where Burton disagrees with Taylor is his point that this shift is a “move from a religious worldview to a secular one.”

Instead, Burton argues that “we have not so much done away with a belief in the divine as we have relocated it. We have turned our backs on the idea of a creator-God, out there, and instead placed God within us—more specifically, within the numinous force of our own desires.”

In a tale as old as Eden, the attempt at self-creation doesn’t lead to deification but to dehumanization. This book shows us how we arrived here—how this moment affects every single one of us in all kinds of ways invisible to us—and how we could start to think of a way to something other than the Kardashian way.

“The story of self-creation, at its core, is not only a story about capitalism or secularism or the rise of the middle class or industrialization or political liberalism, although it touches upon all these phenomena and more. It is, rather, a story about people figuring out, together, what it means to be human. It is a story about trying to work out which parts of our lives—both those parts chosen and those parts we did not choose—are really, authentically us, and which parts are mere accidents of history, custom, or circumstance. It is, in other words, a story about people asking, and answering, and asking once again the most fundamental question human beings can ask: Who am I, really?

“And it is the story of how one answer—in my view, the wrong one—became dominant: I am whoever I want to be.”

5. Tobias Cremer, Godless Crusade: Religion, Populism, and Right-Wing Identity Politics in the West (Cambridge University Press)

With all the Old Testament warnings about idols, we sometimes imagine that these idolatries started with religious exploration—the way a “searching” modern might seek out a new spirituality. In reality, most idol worship started with much more mundane ends in mind: political alliances, military coalitions, marriage compacts. The graven images have changed over the millennia, but this part of it is still true.

This book is about how this dynamic plays itself out right now in the ways that Christian symbols, images, and concepts are co-opted by ethno-nationalist right-wing movements all over the world. For example, Cremer shows how it’s no accident that January 6 insurrectionists saw no contradiction between a “Jericho March” and the “QAnon shaman,” storming the Capitol in the garb of literal paganism. In short, Cremer explores with data how these movements use “Christianity” in order to give transcendent authority to blood-and-soil ideologies about race and nationalism before, ultimately, secularizing or paganizing the supporting religions themselves.

The thinking here is clear, and the warnings are dire. Perhaps most importantly, Cremer does not adopt the sort of fatalistic cynicism that many white American evangelicals display. He shows how some (small “o”) orthodox European Christian leaders and communities actually have succeeded in keeping their religions from being co-opted in this way.

Additionally, I find Cremer’s personal background relevant and motivating: He is the grandson of a Confessing Church pastor who almost lost his life opposing the conscription of the Nazi-era German church into a gospel-less Führer cult.

“Yet, they all saw such Christian symbols as remnants of an identity, community, and home that they had lost through the processes of secularization, globalization, and individualization. Worse still, in the eyes of these protesters, the ‘liberal elite’ (who are in many ways the winners of these processes) were perceived to delegitimize and ridicule their very yearning for community and group identity. National populists have recognized this problem and offered their own remedy: a godless crusade in which Christianity is largely turned into a secularized ‘Christianism’ and a symbol of whiteness that is interchangeable with the Viking veneer, the Confederate flag, neo-pagan symbols or even secularism.”

6. Jonathan Eig, King: A Life (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

I’ve found that I am reluctant to even look at a biography of a handful of figures whose lives seem so well-known that one wonders what else there is to be said. Abraham Lincoln would fit in that category, as would Martin Luther King Jr. This biography is effective precisely because it steals past that sense of familiarity with the kaleidoscopic complexity of an actual person, the story of one who was more than an abstraction of ideals and speeches and movements.

Drawing on interviews and records that were previously unavailable, this biography contributes to the history and the sociology but does not bypass the psychology. In reading this, one can actually start to imagine the sheer exhaustion King faced as he headed into Memphis for those last few days. In fact, by this point in the story, one wonders how a human being could endure that level of exhaustion. The described humanity of the subject—along with the sharp analysis of the context of mid-20th-century America and what led up to it—makes this a biography that will influence the way the next generation sees one of the most important figures in American history.

“Where do we go from here? In spite of the way America treated him, King still had faith when he asked that question. Today, his words might help us make our way through these troubled times, but only if we actually read them; only if we embrace the complicated King, the flawed King, the human King, the radical King; only if we see and hear him clearly again, as America saw and heard him once before.”

7. Esau McCaulley, How Far to the Promised Land: One Black Family’s Story of Hope and Survival in the American South (Convergent)

In a culture like ours, it’s hard to feel the force of what God revealed at Sinai, that we should honor father and mother. That command forces us to confront our creatureliness. No matter what the ambient culture tells us, we actually are not self-created. We came from somewhere; we are part of someone else’s story. Part of what it means to show honor to those who came before us—as well as to show gratitude to the providential God behind all of it—is to conserve and to re-tell those stories.

This book does just that—with beauty and with force. In the blurb for this book, I wrote that I believe it to be Esau McCaulley’s best writing yet. Given what he’s written before, that is really saying something.

McCaulley traces the stories of impoverished tenant farmers in Jim Crow Alabama all the way to his own story in the present day in a way that hits with the force of a great novel. He describes viscerally not just circumstances but emotions and motivations.

Like all good writing, the particularity of this story is what makes it universal. McCaulley describes the human condition when it comes to such matters as mourning the death of a father with whom there was a complicated relationship. I laughed with recognition at his descriptions of learning how to preach—and wondered if he could ever live up to what was expected of him. This book combines gratitude and humility with wisdom in a way that shatters the self-creation myth and drives us to mourning and to celebration, all at the same time.

“I once feared that running was a genetic trait, and that I, too, would leave when my family needed me. So I built a life as the antithesis of my father’s. We were to be two different people, as far apart as the East is from the West. But lives that are connected are not so easily separated. Every hug I give to my children and each sporting event I attend brings with it memories of my own youth. Am I doing these things because I care about my children, or am I trying to prove something to myself? Is it love or some mad experiment?”

8. Beth Moore, All My Knotted-Up Life: A Memoir (Tyndale House)

Sometimes over the past several years, I have felt as though I have a hyphenated name—with the last part being “(not related).” That’s because Beth Moore and I lived through an awful experience together—a sliver of it in public view—and any story that referenced both of us would have to make clear that these Moores weren’t related. The problem is that, precisely because of those shared experiences, I feel like we are related.

As grateful as I always am for Beth, this book made me even more so. From the very first chapter, it is clear that she had no time for public relations or image-building. She writes from the vulnerability of one who has lived through the “knotted-up” realities of such darkness as child sexual abuse, families under stress, and trying to follow God’s call as a woman in some really misogynistic contexts. And yet, with all of that honesty about hard truths, this is a book about joy. Not only does Beth not yield to cynicism—or even almost yield to cynicism—she shows the rest of us how we can do the same.

From the Access Hollywood controversy on, I would often think, “If Beth can get through this, so can I.” I thought the same thing—about a whole range of dangers, toils, and snares—as I read this book. And, though the book is about much more than marriage, I will give this out to engaged couples from now on because of the wisdom here that being “one flesh” doesn’t always mean being “one mind,” and how to love through all of that.

My wife Maria (related) wants me to make the point that, from her point of view, this is one of those books where the audio version is much more than just a way to “consume the content.” I read the book the old-fashioned way, while Maria listened to it too, and she said there’s something especially powerful about hearing not just the story, but the voice telling the story.

“I’m not very sure of myself anymore, if I ever truly was. But I am utterly sure of one thing about my turn on this whirling earth. A thing I’ve never seen. A thing I cannot prove. A thing I cannot always sense. Every inch of this harrowing journey, in all the bruising and bleeding and sobbing and pleading, my hand has been tightly knotted, safe and warm, with the hand of Jesus. In all the letting go, he has held me fast. He will hold me still. And he will lead me home. Blest be the tie that binds.”

9. Mark A. Noll, C. S. Lewis in America: Readings and Reception, 1935–1947 (InterVarsity Academic)

Behind me on my wall right now as I write is a portrait of C. S. Lewis lighting his pipe. For the Christmas season, I’ve added a Santa hat to the top of his head. He would loathe this and would no doubt dismiss it as very American of me, not meaning that as a compliment.

This book examines the question of why so many Americans were (and continue to be) influenced so deeply by this utterly British man. The book speaks with authority, as it is written by one of the truly preeminent historians of our time.

Noll examines how Lewis was received by three American audiences: Roman Catholics, mainline Protestants, and evangelicals. Perhaps surprising to some, for the duration of Lewis’s life, the evangelical audience was the least enthusiastic about him of the three. Noll demonstrates why this was and how it changed. For my fellow evangelicals, many familiar places and names play key roles—Wheaton College, Southern Seminary, Cornelius Van Til, and Elisabeth Elliot.

“An apostle to the skeptics is bound to offend some of the skeptics, which did not seem to bother Lewis in the slightest. (Lewis did, however, take seriously criticism from his own small circle of friends). He thus shows that trying to express what we know to be true, hopefully while enjoying a small circle of sympathetic friends whose critiques we trust, is more important than trying to impress whatever gatekeepers police the higher reaches of our particular fields.”

Perhaps somewhere in the great cloud of witnesses, J. R. R. Tolkien will note that it was not an American who put Father Christmas in the mythos of Narnia, so maybe the Santa hat won’t get me kicked out of the wardrobe.

10. Eugene H. Peterson, Lights a Lovely Mile: Collected Sermons of the Church Year (Waterbrook)

We lost Eugene Peterson, translator of The Message and author of countless books (my favorite of which is As Kingfishers Catch Fire), in 2018, and many of us assumed that we had read our last book from this sage. Long before Peterson was an author, though, he was a pastor and a preacher. The books we read were fermented in the soil of preaching and discipling a specific group of people, Christ Our King Presbyterian Church in Bel Air, Maryland.

This book assembles a series of these sermons, arranged around the church calendar. These messages carry with them what we loved about Peterson: biblical saturation, poetic insight, and the authority that comes with the integrity of a life lived before God. I never expected to be moved and energized by a sermon about Simon Magus, but I was. Included are all those small sentences that stay embedded in my mind because they make the truth resonate in new ways. An example: “To skip reading the Old Testament would be to skip the first thirty-nine chapters of a forty-chapter book.”

“And there are a number of things you can sell in church. You can sell the need of adding an extra dimension to a person’s life. You can sell the importance of Christian education in the lives of children. You can sell the personal benefits of religion. You can sell the need for a new church in this community. But when you get to the center of the church’s life, you can sell nothing, for there it is all given. ‘God so loved the world that he gave his only Son’ (John 3:16). If we persist in our salesmanship at that point, we will participate in the sin of all those priests who have separated people from God and have acted as such miserable substitute gods in individuals’ lives.

“Both buying and selling in the church exist on the periphery. In the center it is all grace, God’s giving himself freely to us and our responding in our poverty to him. And that is not for sale in this church.”

This post was first published in Moore to the Point. Subscribe to get the latest content from Russell Moore in your inbox.