“My libraries are each a sort of multi-layered autobiography, every book holding the moment in which I read it for the first time,” reflected writer Alberto Manguel in his book Packing My Library. “The scribbles in the margins, the occasional date on the flyleaf, the faded bus ticket marking a page for a reason now mysterious—all attempt to remind me who I was then.” I would agree. If it were not for the books that I’ve read, I would be a different person altogether.

And when I, like Manguel, go back through the books I’ve marked up, I sometimes wonder, “What was it that drew me to this book?” or “How did this book change me?” Sometimes I know, but often I don’t.

Each year, I offer up for you my favorite books of the year, those that turned out to be the most meaningful for me over the past twelve months. As I line these volumes up for this project, I find that I learned a great deal about God’s providence over the year past. What was it that I thought I needed to hear or to learn, or to remember. Sometimes these lists give me a clue.

The number of books has fluctuated over the years, sometimes ten, sometimes the number of the year (“15 in 2015,” etc.), but I think I have settled on twelve. Twelve days of Christmas, twelve tribes of Israel; it just seems to work.

As always, these are in no particular order other than where I found them on the shelf as I was writing this.

1) David R. Neinhuis, A Concise Guide to Reading the New Testament: A Canonical Introduction

1) David R. Neinhuis, A Concise Guide to Reading the New Testament: A Canonical Introduction

This is not a “work list” of books so I try not to include biblical studies, theology, philosophy, or ethics here , but sometimes I can’t help it. This little book almost escaped my attention. I didn’t find it on my own, nor did I ever hear about it. The publisher sent me a copy, maybe with a stack of other books. I assumed based on the title and the size that it was what one would expect, a basic list of the major themes of each New Testament book, meant for new Christians or those unfamiliar with the Bible. I thought it wouldn’t be meant for me, but maybe would be something I could recommend to people who were befuddled by how to tell the difference between Mark and Luke, say, or the letters of Peter and those of Paul.

But then I opened the book up, just to scan a paragraph of two, and I was drawn in by this quote: A key quote: “The university frequently introduces students to a Bible they don’t recognize, and the church often teaches students to be devoted to a Bible they don’t know how to read.” Before I knew it, I had read the whole thing, mumbling “Amen” and “good point!” and “I hadn’t thought about that” to myself almost all the way through.

I wrote two posts here on my site about insights from this book, one about the difference between “Bible readers” and “Bible quoters” and one about what the author calls the irreducibility of narrative” as it applies to our morality. This book indeed would help the new Christian trying to navigate the strange new world of the New Testament, but it also will help, maybe even more so, those of us so familiar with the text of the New Testament that we sometimes we sometimes forget just how strange and new and world-reshaping it actually is.

2) Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life Through the Great Books

2) Karen Swallow Prior, On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life Through the Great Books

Speaking of “world-forming narrative,” this beautiful book argues for the “permanent things” that can be discovered, or reinforced, through immersion in really good stories. In this, Prior showcases each of the primary virtues (prudence, courage, kindness, etc.) through immersion in a piece of literature. She does so without turning any of these books into propaganda for “y’all behave.” Instead, she demonstrates how the unique experience of submersion in a text can give us not just cognitive content about virtue but a sort of experience of what these virtues, and their opposites, can be like.

Karen is a friend and I usually try not to include my friends’ books on this list for obvious reasons. I also have a blurb on the back cover, and I try to separate out my endorsements from this list. But, in this case, again, I can’t help myself (is that a lack of prudence? I’ll have to spend some time in The History of Tom Jones to find out).

My endorsement said: “You might not think yourself the kind of person to read a book about reading books. If you’re trying to love people, to work well, to find meaning in your life, this book is for you. Prior guides us through the big questions from great books, with wisdom, insight, creativity, and compassion.” Justin Taylor’s blurb, though, is better: “Prior is the English teacher most of us never had. Few teachers are this clear, compelling, and Christ-centered.”

Amen.

3) Alan Jacobs, The Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis

I would love not to have Alan Jacobs on this list, just for the sake of variety since it seems he shows up on my favorites list every year. But in order for that to happen, he has to stop writing these illuminative, mind-changing books that I inevitably fill up with highlights, notes, and flags. The book uses one year in the midst of World War II to look at the way a specific group of Christian intellectuals—including C.S. Lewis, Simone Weil, W.H. Auden, and T.S. Eliot—addressed the moral and cultural crisis not just of this time of war against fascism, but of what would be left in the peace afterward as well.

As Jacobs puts it, “For these thinkers vexed questions of human nature had to be raised once again, and raised in such a way that a Christian answer to them was made compelling.” To summarize the book here in this small a space would be daunting, given how Jacobs is able to show the unity and diversity of the concerns and proposals of such divergent figures in such compact space. Even those very familiar with the thinkers profiled in this book will find many moments of genuine surprise, both at insights never seen or forgotten, and at how creepily relevant the civilizational and cultural concerns are.

In one aside, I laughed out loud when Jacobs recounted a piece of hate mail a clergyman sent to the magazine that published Lewis’ Screwtape Letters because “much of the advice given in these letters seemed to him not only erroneous but positively diabolical.” Those who have noticed the lack of humor and sense of tone-deafness to irony in our social media era will, maybe, be reassured that such is not completely new.

In the afterword, Stunde Null writes, “If ever again there arises a body of thinkers eager to renew Christian humanism, they should take great pains to learn from those we have studied here: both what they agreed upon and what divided them. But may those future thinkers also be quickly alert to the signs of the times.”

Indeed. And this book will help.

Out of this book came several little serendipities for me, one of which was to re-read Charles Norris Cochrane’s old work Christianity and Classical Culture, and to be reminded how much of still seems prophetic. The other was to track down, from a footnote, a critical edition of Auden’s Advent poem “For the Time Being” that I hadn’t seen. This gave me not only a chance to re-read this sparkling poem just in time for the season, but also led me to a brilliant preface that prompted me to re-think how I viewed the work. It turns out the preface was by Alan Jacobs, who edited that edition. I’m glad I didn’t see it at the time or, no doubt, Alan Jacobs would have shown up, again, on a list of my favorite books of that year.

I haven’t checked, but he was probably already there.

4) Leif Enger, Virgil Wander: A Novel

4) Leif Enger, Virgil Wander: A Novel

Walker Percy once wrote: “Mississippi, with very low sociological indexes, has produced William Faulkner and Eudora Welty; while Illinois and Ohio, with very high sociological indexes produce professors who write books about William Faulkner.” As a Mississippian, of course, I like that. But, left alone, it ignores the rich vein of fiction that has come from the Midwest (though usually from places with what Dr. Percy would describe as “low sociological indexes”). That’s been especially true in recent years, and one of the best is a Minnesotan by the name of Leif Enger (which, if that has not won an award as the most Minnesotan name of all time, it certainly should) .

Enger wrote a well-received novel, Peace Like a River, and another, So Brave, Young, and Handsome, over a decade ago. This one is even better. The book follows a small-town Minnesota movie-theater owner after an accident that leaves him impaired in memory and thought processing. He is essentially seeking to, to use the shopworn old cliché, “find himself” by retracing his own steps. And, in so doing, he enters into the mystery of the lives of some other people who are, it turns out, trying to do the same thing.

Here’s a sample passage: “The message was that I should’ve died, but hadn’t. That was the sense I kept getting. Everyone was nice about it, but I was a living mistake. The notion that I’d somehow put one over on mortality was exhausting.”

The novel is beautifully crafted, and does what good novels ought to do. It takes us into a mind not our own, a place not our own, and shows us, with a sense of mystery and wonder and even awe, what it means to be a human being in a universe like this.

5) Marilynne Robinson, What Are We Doing Here?: Essays

5) Marilynne Robinson, What Are We Doing Here?: Essays

Speaking of great Midwestern novelists, Marilynne Robinson—author of such masterpieces as Housekeeping and the Gilead trilogy—gave us a collection of essays this year, that ranges from the meaning of conscience to a reflection on Jonathan Edwards’ essay on the nature of moonlight to a diagnosis of what has gone wrong in our haywire era to why theology ought to matter to secular people who dismiss it.

Do I really need to convince you to read Marilynne Robinson? If you’ve ever read her, the answer is surely “no.” If you haven’t, you should because she is an expert craftsman of words and an even more expert observer of the world. But I think what I find most compelling about her is that she is honest. She says in this collection, “I think and write about religion because I am religious. It occurred to me early in life that I wanted to align my life with things that seemed true to me.”

Elsewhere she writes, “A society is moving toward dangerous ground when loyalty to the truth is seen as disloyalty to some supposedly higher interest.” I have these words highlighted and underlined to the degree that one can hardly read them, such was my enthusiasm to agree with and to underscore them for myself.

This loyalty to truth means that she is free to critique the arid materialism of contemporary secularism and scientism, the ideological blind alleys of Marxism, and Darwinism, but also the failures of the church. She writes sympathetically of “the large segment of the population who know nothing about religion at all, except what they hear from its very loudest voices, and who are therefore, understandably, secularists.” This does not apply simply to those outside Robinson’s “tribe.” She is a mainline Protestant, a Congregationalist, and yet she dismisses emphatically the tendency to sever the God of the Old Testament from the God of the New. “A great many of us feel an emphatic moral superiority to the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. This is surely bizarre, since to say the least Jesus shows no impulse at all to dissociate himself from him.”

This is a book to remind us written from the soul, to remind us that, even in a disenchanted age, we are souls too, and thus called to faith, hope, and love.

If you want to listen to a conversation I had with Robinson about her writing—especially her fiction—you can listen here.

6) Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other-And How to Heal

6) Ben Sasse, Them: Why We Hate Each Other-And How to Heal

Keeping with the theme of Midwestern truth-tellers is this book by my friend, a United States senator from Nebraska, on the divisions in our country and what’s driving them—loneliness. Ben makes the case that what’s pulling us apart is not exactly tribalism but anti-tribalism—a herd mentality defined by who we are not, by what group we then demonize. The drive to belong fuels the sort of political idolatry we see all around us. And, as always, follow the money because, as Sasse writes, “Contempt is big business” in a time when politics is entertainment and source of transcendent meaning, all at the same time.

Best line in the book: “Part of what it means to be a human being is to have a soul that exists beyond the reach of government.”

Second-best line: “Political addicts are weird. (And there aren’t that many of them. They’re just loud).”

The book isn’t merely a jeremiad against isolation and tribalism. For one thing the book is too fun to really be a jeremiad. More importantly, though, the book doesn’t merely diagnose what’s wrong but also offers hope and suggestions toward cultivating something different. Those suggestions aren’t big national initiatives but instead are small and local and rooted in personal virtue, such as “buy a cemetery plot” and “connect with people, not with your phone.”

This book is honest about our problems, and hopeful about the answers to those problems. If more would heed the call in these pages, we wouldn’t have a perfect country (no society this side of the New Jerusalem will be that). But we would have what the Founders called “a more perfect union.” And wouldn’t that be a welcome change?

The two of us did an event together at the National Press Club in Washington a couple of weeks ago. He talked about the theme of his book, then I offered a response, and then we had a conversation about everything from smartphones to church membership. You can watch it here.

7) Jaron Lanier, Ten Reasons for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now

7) Jaron Lanier, Ten Reasons for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now

In my National Press Club response to the Sasse volume, I cited, multiple times, this next book, written by a Silicon Valley scientist and entrepreneur Jason Lanier. The book deals, in some ways, with predictable issues familiar to the genre: on addiction, attention spans, bullying, and so forth. What caught my attention though was the section dealing with something approaching a disturbing account of human nature, an account that rings true with what I’ve seen both in the digital and the real ecosystems.

We all know that social media platforms amplify the voices of “trolls,” those extraordinarily wounded psyches who seek out such venues to vent their inner demons with anger. Lanier’s argument, though, is not just that social media give a hearing to trolls but that these media are making us all, a little bit, into trolls. He uses a word that is less-than-evangelical-friendly, but that is synonymous with a boorish, mean-spirited, jerk, and says that social media actually can make us into people like this.

Most important, in my view, was his distinction between “pack mode” and “lone wolf” mode in our posture toward the outside world, modes that he argues are being “switched” in us without our ever knowing it.

I didn’t delete all my social media accounts after reading this. But I look at them less, and I look a bit more at what’s happening to us in this age of digital lone wolves, all in pack mode.

8) Seth Godin, This Is Marketing: You Can’t Be Seen Until You Learn to See

8) Seth Godin, This Is Marketing: You Can’t Be Seen Until You Learn to See

Those who know how exasperated I am by the market-driven nature of American religion might find it odd that I would choose a marketing book among my favorites of the year. First of all, I think marketing is just fine, so long as it is not trafficking in such permanent, transcendent matters as divine revelation or the worship of God. But, second, this really isn’t a marketing book. Seth Godin is a sage, pointing just beyond the immediate horizon to the cultural and economic trends remaking the world around us. This book is one more example of that. The book will benefit you if you lead anything, or work in almost any field, but I find there’s some particular application to the life of the church.

Consider the following axioms:

“The best ideas aren’t instantly embraced. Even the ice cream sundae and the stoplight took years to catch on. That’s because the best ideas require significant change. They fly in the face of the status quo, and inertia is a powerful force.”

“We remember what we rehearse. We remember the events we have photos for in our family scrapbook, but don’t remember the events that weren’t photographed. It has nothing to do with the act of taking a picture and everything to do with rehearsing our story, the one we tell every time we see that picture.”

Much of the most value in this book is Godin’s argument that every person “marketing” should do so toward the smallest viable audience. Godin writes:

“The challenge for most people who seek to make an impact isn’t winning over the mass market. It’s the micro market. They bend themselves into a pretzel trying to please the anonymous masses before they have fifty or one hundred people who would miss them if they were gone. While it might be comforting to dream of becoming a Kardashian, it’s way more productive to matter to a few instead.”

Few of us in the church would dream of becoming a Kardashian, but many of us sometimes want to find the key to pleasing everyone with our message or mission. The end result is that we are boring in a way that Jesus never was, and never is. Godin writes. “It’s tempting to make a boring product or service for everyone. Boring because boring is beyond criticism. It meets spec. It causes no tension. Everyone because if everyone one is happy then no is unhappy. The problem is that the marketplace of people who are happy with boring is static. They aren’t looking for better. New and boring don’t easily coexist, and so the people who are happy with boring aren’t looking for you. They’re actively avoiding you in fact.”

That’s an important word for people who are charged with stewarding the explosively good news of the inbreaking of God’s kingdom. The boring status quo of nominal cultural Christianity, without the alarming vitality of the cross and the gospel and the lordship of God, isn’t looking for anything else. But Godin would tell us there is out there a tribe that might well listen. God would call it, in this case, a remnant. And from remnants God creates multitudes, numbers that no man can number.

Godin is a quick and fun read. Note how he ties his argument together with observations about why Moby Dick has some one-star Amazon reviews, why it was smart for Facebook to start at Harvard, and why the Grateful Dead never had a number-one hit on top-40 pop radio (and should be glad they didn’t).

9) Maxwell King, The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers

9) Maxwell King, The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers

If you’ve been waiting for a book about what Mister Rogers would do when he found that his children had installed a marijuana greenhouse in his basement, then do I have the book for you. That is a tiny part of this new biography of the children’s television pioneer Fred Rogers, of course. But I was drawn to the vignettes of Rogers as parent. The author quotes his children saying that he would sometimes take on the voices of his Neighborhood-of-Make-Believe puppets based on his mood: “If it was King Friday’s voice that meant I had really stepped too far out of bounds.”

The book is a welcome read because it is not hagiography. Rogers is presented as hard-driving, with something of a temper. Staff members would sometimes remind one another, “’Whose Neighborhood is it? Not yours.” The book shows some of his foibles and failures and frustrations both personal (see the marijuana anecdote above) and professional (he tried to do an interview program for adults, and flopped).

But all of that is minor compared to the genius the man was, both in terms of television innovation and, more importantly, in connecting with children. This biography shows how Rogers honed the craft of talking to children, on the air, about everything from the death of a goldfish to the assassinations of political leaders, from the civil rights movement to showing children that they couldn’t actually go down the drain in the bathtub as they might fear. Those of us who came of age at a certain time cannot help but read this book with the sound of trolley-bells in the background of our minds.

The main takeaway, as I see it, from this man’s life was that he took children seriously. In that, he modeled one who spent time with children when his own disciples thought them a waste of his time, and who elicited from them songs that made the religious leaders indignant at their audacity. I came away from this wondering not so much how can we do television better for children, but rather asking how I can listen more carefully to the children around me.

Mr. Rogers was from a far more mainline Protestant denomination than what I would embrace, but he did express faith in Christ, and we are all justified by faith, not by the theological acumen of our respective church memberships (and for that we should all be thankful!). That realization brought a sense of joy to mind as I read the closing accounts of his death, that this was not the end of his story.

And it’s such a great feeling to know he’s alive.

10) Gary Moon, Becoming Dallas Willard: The Formation of a Philosopher, Teacher, and Christ Follower

10) Gary Moon, Becoming Dallas Willard: The Formation of a Philosopher, Teacher, and Christ Follower

The other biography that moved me far more than I expected this year was this one, a look at the life of Christian philosopher Dallas Willard. “Dallas Willard’s life deserves serious study because he became a man who experienced authentic transformation of life and character,” the author writes. “It only took a few minutes of watching his life to know that ‘he lives in a different time zone than the rest of us.’”

The start of the story is sad: “A mother who left him before a single memory of her could be clearly formed; a father who, despite his best efforts, was a disappointment; and a beloved older brother who taught him to swim by leaving him in what Dallas believed to be snake-infested waters. It is not surprising that Dallas became a boy who tried to cut wood just right in hopes that he would be asked to stay.”

Such a background, of course, could lead one to spend a life seeking to earn favor, maybe even with God. But in the case of Dallas Willard, grace intervened.

The book takes us through Willard’s days of disappointment as a failing pastor in a Missouri Baptist church, on through his academic career in philosophy, toward where he ended up, as a teacher of the broader Body of Christ of what it means to live, in-the-now, in the kingdom of God. The book deals honestly with Willard’s struggles with his ego, and with the pressing demands of his schedule versus his family. But the main focus of the book is what is quite obviously Willard’s grasp of the reality of the love of God.

I have found myself fighting back tears reading, many times, but rarely when reading a biography, and certainly never reading the biography of a philosopher. Maybe it was the time in my life, but I came undone when I read the account of a frail, elderly Willard praying the Aaronic blessing—and teaching his way through it, to a congregation of people:

“Just think about saying it to another person as you look into their eyes, ‘God bless you and keep you.’ Emphasize you. ‘God make his face shine down upon you.’ There is so much about the face of God in the Bible. One of the most precious thing that we can have is living before the shining face of God. Now, if you have trouble with the shining face, find a grandparent somewhere and watch their face shine on their grandchild; that can give you a little idea.”

The author noted that few wanted to leave the room after that. “They had experienced what this loving man from rural Missouri had been teaching: that when you pray, Jesus will come right up to you, look right at you personally, and share with you knowledge for how to live your life in full.”

Underneath this I can see that I scrawled in pen: “Remember what these words did for you 4/5/18.”

Likewise, the ending of this book moved me to tears, in the description of Willard’s death, and especially, in the letter to his wife, written in the waning days of his life. In the letter, Willard speaks of his gratitude to God for his childhood in Missouri, for books and words, for Sunday school and church taking him to the grace of God in the gospel, and his gratitude for life with her. He also apologizes. “I know that grace has kept me thus far from hurting you even worse than I have, but also it has ‘permitted me’ to be rather inhuman—counting on the religious basis of our relationship to prevail where I didn’t know what to do or didn’t want to do the kind thing.” He concludes with a testimony to his wife’s beauty, his love for her, and his gratitude to God for it all. Then the words at the end of the letter: “Enough already! But it’s all true.”

It’s all true.

I wiped away tears just thinking of it again. This book is well worth your time.

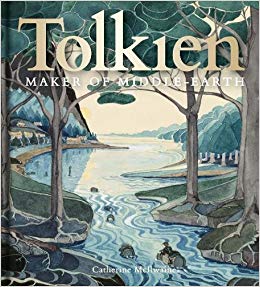

11) Catherine McIlwaine, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth

11) Catherine McIlwaine, Tolkien: Maker of Middle-earth

In writing this list every year, I will keep the stack of books on the table in front of me, picking up each one and flipping through, reminding myself of what I marked or highlighted or flagged therein. Doing that with this book cost me a good half hour because I found myself lost in the drawings and text within for so long, just as if it were the first time I had seen it.

For those of us who have loved Tolkien, many of us since we were children, this book is a treasure. Published by Bodleian Library, this beautiful coffee-table book is filled with essays about various aspects of Tolkien’s life and work, copies of handwritten notes and manuscripts by him, drawings and maps of his ideas coming to life, letters to correspondents far and wide, and photographs. I especially loved the photographs of Oxford, specifically the route taken in walks by Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis. “Not all who wander are lost,” indeed.

The essay on how Tolkien managed his time in order to write is itself worth the price of the book. And almost every page is just as delightful and informative.

Reading this book is an immersive experience and, as I said, can cause time to get away from one, if one is not careful. But isn’t that one of the delights of good books? Last year, I started to re-read the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but halfway through Fellowship I was drawn away to something else, and dropped off. Even so, I was astounded by how much I had forgotten, so much gleaming with truth and goodness and beauty, even in a book I’d read multiple times over my life. This book has prompted me to pick up once again on the journey with Frodo in the new year.

If you are or if you have friends who are, like me, hobbits at heart, and you are wondering what to get them for Christmas, I have an Inkling as to where you should start.

12) Action Comics: 80 Years of Superman

12) Action Comics: 80 Years of Superman

If you ever visit my home study, you will see all sorts of things you would expect on the walls around you. There are Biloxi Seafood Festival signs, a Merle Haggard concert poster, some framed Charles Spurgeon sermon notes, a Walker Percy portrait, a yellowed old graduation picture of the 1919 graduating class of Southern Seminary, a framed tweet by a president of the United States giving his views on the condition of my heart (Fact check: true, cf. Jer. 17:9), and so on. Right in the middle of all that, there’s a metal reproduction of Action Comics #1, with the familiar image of Superman, lifting a car above his head.

Those of you who know me will know that I have been, from my earliest memories, a fan of the man from Krypton (I talk about why here). 2018 is the eightieth-anniversary of the Man of Steel’s creation by two Depression-era Jewish kids from Cleveland, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster. So how could I not include Kal-El in this list? There was, of course, much to choose from this year. And Action Comics has hit this year issue 1000, with a large commemorative edition done for the occasion. Alongside that issue, though, was this one. I chose it because it combines reprints from the past eighty years, alongside essays by thinkers such as Jules Feiffer and journalist Larry Tye about why the Superman mythos persists.

This is a good memorial addition for those of us who admire the Smallville native, and maybe a good jumping on point for those who want to catch up with what been going on in Metropolis lately.

Alongside this, Brian Michael Bendis came over to DC from Marvel Comics, with much fanfare this year, to write both the Action Comics and Superman titles. The trade collection of his initial Man of Steel run was also released this year. I’ve been reserving judgment because of fears that Bendis might wipe out of continuity what I think is the best thing that has happened to the character—his marriage to Lois and his fatherhood of Jon. So far I’m still on board (but don’t mess with the wife and kid, Bendis).

Alongside this commemorative book, DC has republished some trade paperbacks of two of what I consider to be the best Superman stories of all time, Geoff Johns and Gary Frank’s Superman: Secret Origin and Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman.

And since it is the fortieth anniversary also this year of Superman: The Movie, be sure to play John Williams’ score in the background and see if you don’t feel ready to take on anything, anything but Kryptonite.

For obvious reasons, I do not include books written by myself or ERLC staff in this list. If you are interested in the books published over the course of the past year (and a bit earlier), you can go here.