One of my earliest memories is of a substitute Sunday school teacher chastening me for putting a coin in my mouth. “That’s filthy,” she said. “Why, you don’t know if a colored man might have held that.” It might just be my imagination playing tricks on me, but it seems as though she immediately followed this up with, “Alright children, let’s sing ‘Jesus Loves the Little Children, All the Children of the World.’”

Now, this lady probably didn’t consciously think of herself as a white supremacist. She almost certainly didn’t think of herself as subversive of the gospel itself. She never thought about the hypocrisy of holding the two contradictory worldviews together in her mind. She probably didn’t see how her dehumanizing of African-Americans was a twisted form of Darwinism rather than biblical Christianity.

She wasn’t alone.

On the question of civil rights in the American Christian context, there is little question that, with few exceptions, the “progressives” were right, often heroically right, and the “conservatives” were wrong, often satanically wrong. In the narrative of the dismantling of Jim Crow, conservatives were often the villains and progressives were most often on the side of the angels, indeed on the side of Jesus.

The question is not whether the progressives won the argument or whether they should have won the argument; the question is why they were persuasive, ultimately, on this point (and almost no other) to their more conservative brothers and sisters. The turnaround is striking, perhaps nowhere more clearly than in my denomination, the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), where a generation ago most conservative leaders were segregationists.

Some, of course, will claim cynically that conservative evangelical leaders, like some national politicians, don’t play with racial demagogy anymore because such appeals don’t “work” anymore in 21st century America. Nobody wants to be seen as a racist. Well, okay, but, even if one accepts that argument, why is it true that a segregationist would be barred (and rightly so) from speaking at the SBC Pastors’ Conference of 2013 and wouldn’t be at the SBC Pastors’ Conference of 1950? Isn’t it because the people wouldn’t tolerate it? Well, why the change? It must be more than just changing American culture since conservative evangelicals have been in the throes of a much-hyped “culture war” on all sorts of issues since the 1960s?

Why is civil rights no longer a “culture war” issue? Why were the voices of the civil rights pioneers persuasive, not only to mainstream America but to conservative Christians as well? Some might argue it is because the culture has changed. But the culture has changed just as much (if not more so) on the question of gender and sexual issues, after three waves of feminism and a sexual revolution, but not so for traditionalist Catholics and confessional Protestants.

The reason SBC progressives, and the larger civil rights movement, were persuasive was because of the mode of their argument. The progressives, as scholar David Chappell shows in his book Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow, appealed to biblical orthodoxy and missionary zeal in their arguments, not simply to the arc of historical progress.

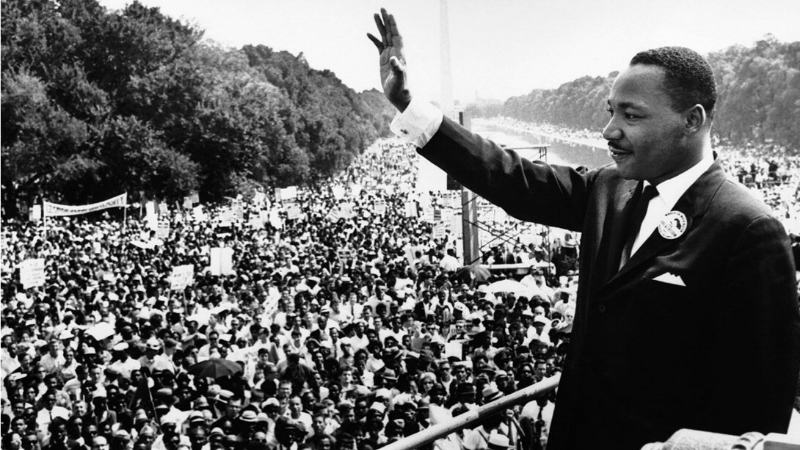

This is true at the macro level—think of the King James Version of the Bible woven so intricately into the themes of Martin Luther King’s speeches and sermons. It is also true at the micro level. SBC civil rights advocates—from Foy Valentine to T.B. Maston to Henlee Barnette—argued from decidedly conservative biblical concepts.

The civil rights movement struggled on multiple fronts. In the political sphere, leaders such as King pointed out how the American system was inconsistent with Jeffersonian principles of the “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights.” Politically, Americans had to choose: be American (as defined in the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence) or be white supremacist; you can’t be both. King and his compatriots were right.

But the civil rights movement was, at core, also an ecclesial movement. King was, after all, “Rev. King” and many of those marching with him, singing before him, listening to him, were Christian clergy and laity. To the churches, especially the churches of the South, the civil rights pioneers sent a similar message to the one they sent to the governmental powers. You have to choose: be a Christian (as defined by the Scripture and the small “c” catholic apostolic tradition) or be a white supremacist; you can’t be both. They were right here too.

How can white supremacy be true, they would argue, if humanity is made from “one blood” in the creation of Adam? How can one segregate evangelistic crusades if the cross of Christ atones for all people, both white and black? If God personally regenerates repentant sinners, both white and black, how can we see people in terms of “race” rather than in terms of the person? If we send missionaries across the seas to evangelize Africa, how is it not hypocrisy not to admit African-Americans into church membership?

The biblical power of the argument is true, regardless of whether all the civil rights pioneers, in the SBC and out of it, believed in biblical orthodoxy.

Many did. See the faithful heroine Fannie Lou Hamer of Sunflower County, Misssissippi, for example. If Baptists had a means of canonization, I’d support it for her. I still claim the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party as my partisan home, and I say expand the “freedom” to the unborn as well as the born, even though the party doesn’t exist anymore.

But regardless of personal faith, the civil rights heroes indicted conservative hypocrites, prophetically, with the conservatives’ own convictional claims. And, as Jesus promised, “My sheep hear my voice and they follow me.”

The arguments for racial reconciliation were persuasive, ultimately, to orthodox Christians because they appealed to a higher authority than the cultural captivity of white supremacy. These arguments appealed to the authority of Scripture and the historic Christian tradition.

This authority couldn’t easily be muted by a claim to a “different interpretation” because racial equality was built on premises conservatives already heartily endorsed: the universal love of God, the unity of the race in Adam, the Great Commission and the church as the household of God.

With this the case, the legitimacy of segregation crumbled just as the legitimacy of slavery had in the century before, and for precisely the same reasons. Segregation, like slavery, was shown to be what all human consciences already knew it to be: not just a political injustice or a social inequity (although certainly that) but also a sin against God and neighbor and a repudiation of the gospel. Regenerate hearts ultimately melted before such arguments because in them they heard the voice of their Christ, a voice they’d heard in the Scriptures themselves.

Conservative Christians, and especially Southern Baptists, must be careful to remember the ways in which our cultural anthropology perverted our soteriology and ecclesiology. It is to our shame that we ignored our own doctrines to advance something as clearly demonic as racial pride. And it is a shame that sometimes it took theological liberals to remind us of what we claimed to believe in an inerrant Bible, what we claimed to be doing in a Great Commission.

A version of this article originally ran on January 18, 2010.