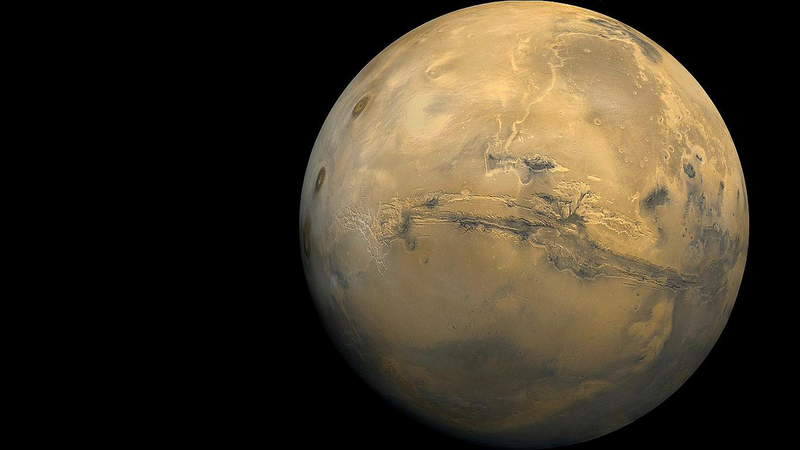

For the last several weeks many of us have been tuned into the latest reports from NASA about Mars. Technology has allowed scientists access to the red planet in ways unfathomable even just a decade ago. From details about Mars’ climate to evidence of water on the planet surface, a number of questions have been raised about the worlds that neighbor our own.

Perhaps for many of us, the images and descriptions of environments literally years away from earth might cause a little anxiety. What all is out there? How much of it? If our little galaxy is just a pin-point in a vast, swirling universe, then why would we think that what happens on this microscopic rock matters all that much? In the sweep of cosmic space, why would your life and my life have much purpose at all?

Secular philosophers and scientists have tried answering this question. Some, like the late Christopher Hitchens, say there is nothing special about humanity and it is immoral to think otherwise. Others, such as Neil deGrasse Tyson, say that because humanity is nothing more or less than a part of the physical world (through evolution), what’s true about the cosmos is the true about people. That’s a slightly more romantic answer than the one offered by Hitchens, but in truth, both explanations lead to the same ultimate conclusion: The universe is huge, and we are small, just because.

But the Bible has a different answer. Scripture understands that human beings have a tendency to feel small in light of the universe around us, but the biblical explanation begins where the materialistic explanations end. After all, a material connection with stardust doesn’t a personal connection make. The universe doesn’t know I am here, and doesn’t care where I’m going, if the universe is just stuff.

In a Christian vision of the cosmos, the vastness of the universe around us isn’t incidental. God is designing the universe this way to reveal something (Rom. 1:20), something about himself, something about his gospel. David, king of Israel, felt small when he looked into the expanse of the night sky, a reaction the Scripture considers to be reasonable (Ps. 8:3). The starry scene above made him wonder, “What is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?” (Ps. 8:4). And David didn’t even see a pinprick of what we now see is out there. Conversely, we see only a pinprick of what our descendants may know about what’s out there.

The universe is meant to prompt such a response precisely so that this can be met by a revealed word: that humanity is “crowned with glory and honor,” and that God has set all things “under your feet” (Ps.8:5-6). That reality cannot be seen through the natural order alone. Sure, we can see the dignity of humanity over against the beasts and the birds. We recognize our intellect, our moral sense. But what about us seems “crowned with glory and honor” in light of the star systems and black holes light years away from us? We don’t yet see all things under our feet, the book of Hebrews tells us, and that’s the point.

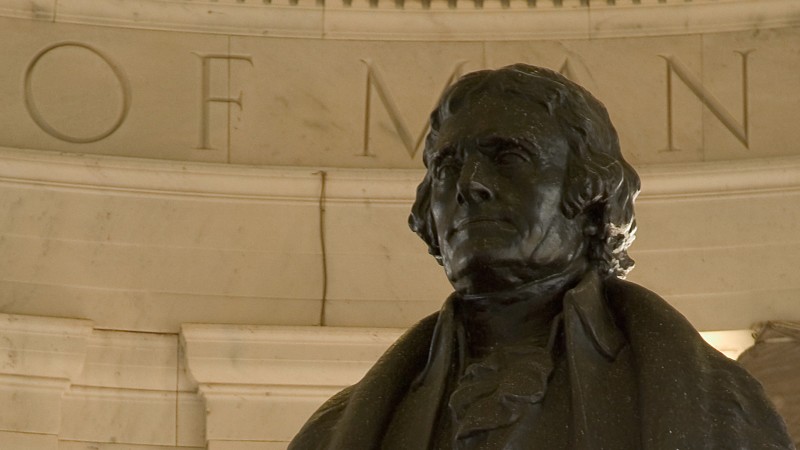

“But we see him who for a little while was made lower than the angels, namely Jesus, crowned with glory and honor because of the suffering of death, so that by the grace of God he might taste death for everyone” (Heb. 2:9). The central point of the cosmos is Christology. All things are summed up in this man, Christ Jesus (Eph. 1:10). Even from the perspective of the territory of Israel, much less the Roman Empire, the background of this man was surprising. God chose the Light of the cosmos to dawn not out of Rome or Athens, or even Jerusalem, but from Galilee.

The natural universe is not merely a mute accessory to our lives. In Christ, the very mud of the earth is joined to the eternal nature of God so that the material creation is joined—without conflation or separation—to the Person who is the center and purpose of all of history. This means that nature is, in fact, permanent—more permanent than any naturalistic account could conceive. “God has much more in mind and at stake in nature than a backdrop for man’s comfort and

convenience, or even a stage for the drama of human salvation,” evangelical theologian Carl F. H. Henry asserted. “His purpose includes the redemption of the cosmos that man implicated in the fall.” In other words, Jesus came not to bury the earth, but to raise it.

The vastness and beauty of the Milky Way should elicit a response from us. That response should be neither one of pagan nature worship nor greedy utility, but of wonder and awe at Christ Jesus in his infinite vastness and immeasurable beauty. We should likewise marvel at the truth that a God in charge of galactic orbits chooses to live with and in us. We are not adopted into Christ despite our smallness, but indeed on account of it. If the unveiling of Christ was met with a dismissed, “Can any good thing come out of Nazareth?” (Jn. 1:46), should we really be surprised that God, at even the cosmic level, chooses what seems insignificant and tiny to display the paradox of the wisdom and power of God in Christ (1 Cor. 1:20-31)?

The universe is meant to make us feel small, to stand in silenced awe. The gospel, though, tells us that we have purpose and meaning, not by our strength or our power, but because we’re hidden in the One who was dead, and is now alive forever, the One for whom every galaxy, seen and unseen, was made as an inheritance.

__________________

Image Credit, licensed under CC 2.0. (resized)